Climate at the Crossroads: Why Good Governance Is Our Greatest Climate Solution

May 29, 2025By Gerselle Koh, 2025 Future Blue Youth Council member

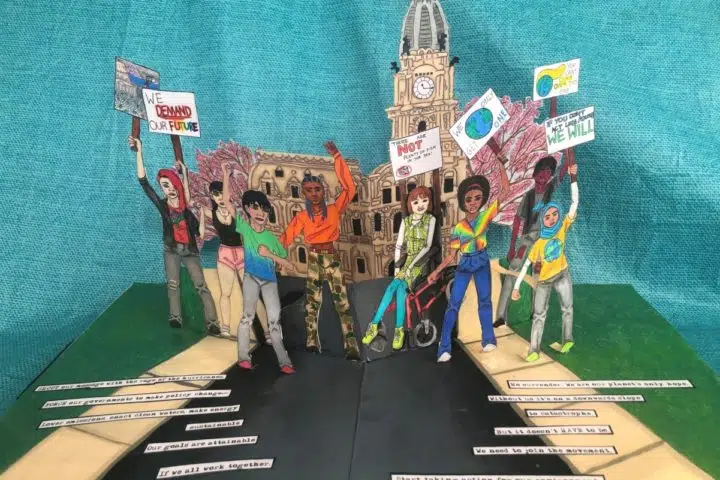

Cover photo: Call to Action, Red Whelan, 2020

In just 100 days, sweeping environmental protections can be dismantled, undermining decades of progress with the stroke of a pen. This is not a hypothetical scenario. During the first 100 days of Donald Trump’s administration, 145 actions were taken to undo regulations designed to protect clean air, water, and a livable climate — more rollbacks than during his entire first term as U.S. president.

This highlights a truth that is often overlooked: governance is what determines whether climate action succeeds or fails. While technological innovation and activism are critical, they cannot thrive without strong political institutions. Without the backing of good governance, progress can stall or, worse, be reversed. Good governance isn’t just a supporting factor in the climate fight, it’s the foundation upon which climate action must be built.

What Is Good Governance in a Climate Context?

Good governance in a climate context requires more than efficient administration, it requires governments to integrate climate considerations into all aspects of leadership and policy making. These eight key principles form the foundation of good climate governance:

- Climate Accountability – Governments are responsible for safeguarding the well-being of their people and ecosystems, including accountability for climate-related risks and opportunities. As climate change increasingly threatens national security, economic stability, and public health, government leaders have a duty to act using the best available evidence to ensure resilience across all sectors.

- Command of the Subject – Government leaders should demonstrate strong climate literacy or have access to expert guidance. Informed understanding of climate science, economics, and social impacts is essential for informed decision-making.

- Government Structure – Climate action should be embedded into the institutional framework of government. This includes establishing dedicated climate departments, embedding climate responsibilities across existing departments, and ensuring coordination across all levels of the government.

- Material Risk and Opportunity Assessment – Governments should regularly assess the material risks and opportunities posed by climate change across sectors such as agriculture, infrastructure, energy, and health. This includes using climate modelling, vulnerability assessments, and stakeholder engagement to inform policy.

- Strategic Integration – Climate objectives should be integrated into national development strategies, budgetary planning, and economic policy. Long-term strategies should also align with commitments such as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and net-zero targets, particularly in sectors like energy and land use.

- Incentivisation – Governments should align public sector incentives, subsidies, and procurement practices with climate goals. This includes rewarding low-carbon innovation, phasing out fossil fuel subsidies, and integrating environmental metrics into public sector performance evaluations.

- Reporting and Disclosure – Governments should report on climate progress through national inventories and international frameworks like the UNFCCC to ensure transparency. Disclosures should also be regular, data-driven, and publicly accessible, allowing civil society and stakeholders to hold government leaders accountable.

- Exchange – Governments should engage actively with other countries, local authorities, Indigenous groups, civil society, scientists, and youth. Meaningful exchanges build trust and ensure climate policies reflect diverse perspectives.

Lies, Irene Raeeun Kim, 2018

Lies, Irene Raeeun Kim, 2018

Good Governance in Action

Globally, several countries offer concrete examples of how good governance can drive sustained climate action.

Sweden has shown that climate leadership can be institutionalised. In 2017, its Ministry of Climate and Enterprise established a comprehensive climate policy framework that includes legally binding climate goals, a climate act, and an independent climate council. This framework mandates that climate policy be integrated into financial and policy planning, while government agencies are held accountable for emissions reductions. Since its implementation, Sweden’s per capita CO₂ emissions dropped from 3.32 tonnes in 2017 to 2.91 tonnes in 2019. Its participation in the EU Renewable Energy Directive alongside other Nordic countries further reflects regional coordination for a net-zero future.

Chile has likewise made significant governance reforms. In June 2022, it passed the Framework Law on Climate Change, committing to carbon neutrality by 2050. The law requires all ministries to integrate climate considerations into their planning and budgeting, with progress reviewed every five years. It also mandates a registry for pollutants, establishes sector-specific adaptation plans for climate-vulnerable regions, and protects the ozone layer through regulation of harmful substances.

Each of these examples demonstrates that climate action can succeed when rooted in governance structures that prioritise accountability, transparency, and long-term planning.

When Political Agendas Undermine Climate Action

However, where governance falters or is co-opted by political agendas, climate progress can rapidly unravel.

The resurgence of climate obstructionism in the U.S. under a second Trump administration illustrates how governance can be weaponised to halt environmental progress. Through executive orders, agency memos, and policy changes, his administration erased much of the climate progress made under Joe Biden. Climate funding was frozen, the U.S. withdrew from the Paris Agreement, and pollution standards were rewritten. Vast swaths of land, including parts of the Arctic, were opened up to oil and gas drilling, while commercial fishing resumed in previously protected ocean sanctuaries. Half of the U.S. national forests were put at risk of being cleared for timber, laws protecting endangered species were loosened, and national monuments were slated to be shrunk.

No longer relying solely on overt denial, the administration embedded climate skepticism into government institutions. This was exemplified on a single day, March 12, when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced 31 separate rollbacks to pollution standards, which had been projected to save up to 200,000 lives. Among them was a proposal to reconsider whether greenhouse gases pose a threat to public health, a move that undermines the very legal basis of many existing climate regulations.

Yet the issue is not confined to one country. Across the world, the absence of good governance similarly weakens climate commitments. In Brazil, under President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, environmental protections were systematically weakened, enabling a surge in illegal logging, land grabbing, and mining in the Amazon. Deforestation in the rainforest reached a 15-year high in 2021, with over 13,000 square kilometers of forest lost in that year alone. Bolsonaro also dismantled the enforcement capacity of the Ministry of Environment, removing its ability to monitor and penalise environmental violations. Although he is no longer in office, the institutional damage he left behind continues to threaten one of the world’s most critical carbon sinks.

In many climate-vulnerable countries where adaptation and mitigation funding is urgently needed, corruption further impedes progress. Despite inflows of international climate finance, poor governance, characterised by a lack of transparency and entrenched patronage systems, often leads to misallocation or embezzlement of funds. Between 2012 and 2021, the ten largest recipients of climate finance all scored below the global average on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). In Papua New Guinea, US$2 million was misappropriated from the Climate Change and Development Authority, while in Russia, millions vanished from a United Nations Development Programme-managed US$7.8 million emissions reduction project. These examples highlight how corruption and poor governance can derail urgently needed climate action.

Governance Is a Climate Solution

Climate action does not exist in a vacuum. It is shaped, enabled, or obstructed by the institutions that govern it. The difference between a livable future and escalating catastrophe may not come down to technology or activism alone, but to whether governments rise to the responsibility of leading with integrity. As we invest in renewable energy and mobilise climate movements, we must also invest in political systems that support long-term leadership. In a world facing climate breakdown, the question is no longer just what we do, but who we trust to lead us forward.

Sources

Executive Action Review: The First 100 Days of Trump’s Environmental Policy. (2025). The Federalist Society. https://fedsoc.org/commentary/fedsoc-blog/executive-action-review-the-first-100-days-of-trump-s-environmental-policy

World Economic Forum. (2019). Principles for effective climate governance. Climate Governance Hub Climate Governance Initiative. https://hub.climate-governance.org/article/principles-for-effective-climate-governance

Jansen, C. (2023). 3 leading countries in climate policy. Earth.Org. https://earth.org/countries-climate-policy/

Spring, Jake & Boadle, Anthony. (2021). Brazil’s Amazon deforestation surges to 15-year high, undercutting government pledge. reuters.com. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/brazil-deforestation-data-shows-22-annual-jump-clearing-amazon-2021-11-18/

How Corruption Undermines Global Climate Efforts. (2025). Transparency International. https://www.transparency.org/en/news/how-corruption-undermines-global-climate-efforts