Storytelling and Saving the World

June 16, 2021By Jude Strelitz-Block, Future Blue Youth Council member

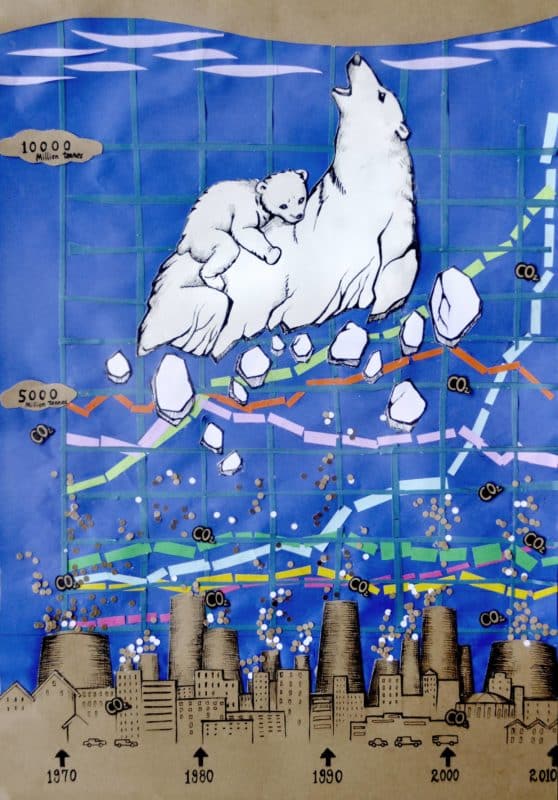

Featured artwork: “Harder to Breathe, But Easier Together,” Victoria Lai, Massachusetts

As stories continue to emerge about disruptive behavior in certain public spaces like airplanes due to some people’s resistance to coronavirus public safety measures—namely, mask wearing—our collective hand-wringing continues: When did science become so political? Why won’t people make the basic behavioral changes necessary to protect our communities and bring an end to the pandemic state of emergency?

For climate scientists, however, individuals’ unwillingness to acknowledge the validity of science, much less modify their daily routines to confront an existential threat to survival, is nothing new. When Katharine Hayhoe, a climate researcher at Texas Tech University, was interviewed by the Washington Post in August of 2020, she affirmed this: “Climate scientists were probably the least surprised people in the world when the response to the coronavirus became politically polarized. Because that’s what we’ve been living through for 30 years,” she said.

Indeed, engaging the public around climate change has been historically difficult to accomplish.

However, amidst the devastation of the coronavirus have been some paradoxical beacons of hope for environmentalists: the pandemic’s dramatic and calamitous impact on global economics revealed both the corrosive effect of unmanaged economic growth on the environment—and the tantalizing notion that this damage is reversible. In March and April of 2020, our coronavirus anxiety was tempered by images of the dank canals of Venice running clear and the Himalayan mountains visible for the first time in three decades in Northern India.

But perhaps most significantly, we have all been witness to a fascinating experiment in how to communicate about urgent threats to our survival so that (skeptical) people will listen.

Strategies that don’t seem to work: messaging that over-relies on data—especially when the “numbers” about infection rates or “new climate normals” are disconnected from specific contexts, people, and places. We’re just not good at processing information this way. It doesn’t move us. Or motivate us. Also, judgmental messaging that seeks to inspire responsiveness by labeling people as “good” or “bad” based on their specific behaviors (mask-wearing, say, or recycling). This kind of messaging can even erode new pockets of potential support. People don’t react well to being shamed.

Strategies that DO work: simple and candid discussions of the issues, particularly when they are accompanied by accessible visual representations. Pie charts are apparently especially well-received by the public. Metaphorical reflections on the existential threats we face—not so much.

“Amidst Our Emissions,” Chelsea Hu, Virginia

Above all, though, personal storytelling is surfacing as our most effective tactic for not just enhancing the public’s awareness of the need to protect our oceans or prepare for weather extremes, but engaging people in the work of changing their behavior. Studies have shown that we connect most strongly with messaging that highlights the consequences of global warming on particular individuals and specific places.

Some hot tips for using storytelling to move people:

- Be creative: people tend to pay attention to novel formulations of accustomed messaging.

- Show, don’t tell: the audience’s connection to the character will drive their engagement.

- Experiment with new written, oral, and visual mediums: no one approach appeals to everyone, and we all are surprised sometimes about what resonates with us.

Here is where Bow Seat’s mission to provide teens a space to “connect, create, and communicate for our ocean” through art and storytelling becomes more than just a showcase for rising talent—but an instrument of social change.